As I sat in the Active Learning Lab and observed Jordan Walker's biology class construct their microscopes, I couldn't help but grin.

Back in 2005, when I first embarked on my career in education, I recall the effort administrators and teachers put into preventing students from using their phones. In Dublin, to avoid any chance that students would be unable to resist the temptation of their device, students were asked to leave their phones inside their lockers. In Upper Arlington, even though students have been able to keep their phones with them for as long as I've taught in the district, they were discouraged from pulling them out during class.

Though the rigid phone rules have softened some over the last few years, the Upper Arlington Student Rights & Responsibilities Handbook still states that "Students may use wireless communication devices (WCDs) before and after school, during their lunch break, in between classes as long as they do not create a distraction, disruption or otherwise interfere with the educational environment, during after school activities (e.g. extra-curricular activities) and at school-related functions."

It still paints a picture of phones as an obstacle to learning.

And it still suggests they should only be used outside of an educational environment.

But what if devices were actually central to the educational environment?

What if phones were just as vital as paper, pens and books?

In an effort to make use of resources, many teachers at Upper Arlington High School have found productive and innovative ways to incorporate what was once the enemy into the fabric regular classroom instruction. From surveys and quizzes, to study apps and vocabulary apps, potential uses vary from course to course, but what Jordan Walker did last Monday in her biology class, seemed to take the concept of phone-as-an-educational-tool to a whole new level.

She showed her students how they could use their device to literally magnify life.

At the start of class, Ms. Walker asked students to get into pairs and then she passed out materials and instructions pre-packaged by her former Metro School colleague, Dr. Andy Bruening, who, in conjunction with working for Metro School is also the PAST Foundation's Director of Bridge Programs. Walker said that Bruening showed her a picture of what he was doing with his students and she presented the idea to her department. Inspired by the prospect of what the activity could unlock for students, her department secured funding to purchase supplies so every biology class had access to the experience.

Once students had their supplies, she told them they would be constructing microscope platforms so they could use their phones to explore specimen slides located at the back of the room.

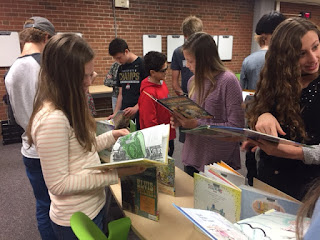

Groups worked at their own pace, discerning instructions, spinning screws, lining up boards. Some took the entire period to put the platforms together. Others flew through the directions quickly and found themselves with ample time to gaze at samples ranging from grains of sand, salamander tails and blood smears, to a cross-section of a chick cell.

While all groups worked at varying paces, regardless of their microscope construction speed, the number of slides they viewed, or whether or not they were able to estimate the level of magnification, all groups had the experience of making something--of grappling with the challenges of building--of following a third-party's set of directions, pulling pieces from a bag and determining how to put them together in an effort to make something magnificent. They experienced what it was like create a device and then use it, rather than merely walking up to an already manufactured device and taking the existence of it for granted.

As I watched students manipulate the hardware, the boards and yes, their cell phones, I was terribly moved by the power of innovation, by the prospect of imaging what could be and allowing students to see the ways those what-if ideas could become reality. I was moved by the fact that these students had the chance to use their fingers, their eyes and their brains to create a lens through which they could look at the world, and I am enormously excited for the potential of what's to come.