By Laura Moore

|

"I love learning, but the last time I loved school was elementary school."

For as long as I live, I'll never forget her words, her face, the confession she gave as she sat in front of 27 of her peers, 16 teachers, a counselor and an administrator at a Design Thinking Workshop in the Graf Center yesterday.

Her words inspired all of us to dig deeper, to open up wider, and to connect more meaningfully with each other as we, collectively, shed our inhibitions, broke patterns, and imagined ways we could bring joy back to the classroom.

Before we got to that point though, Daniel Paccione, the IB Coordinator and Director of Global Studies for EF Academy in New York, Oxford and Torbay, invited us to participate in several ice-breaker activities where teachers and students drew one another in 30 seconds, determined how to get from point A to point B on a image he projected, identified the what, how and why in another image, and reflected on how we are creative and what motivates us to solve problems.

Throughout these exercises, Paccione reminded us of the value in diverse ways of thinking and experiencing the world, and he encouraged us to appreciate the value we bring to the process of creative problem-solving. As he did this, he also worked to dispel the myths of creativity: that only some people and some ideas are creative, that something has to be complicated or important to be creative, and that creativity is stifled by school.

Paccione then led us through the six stages of design thinking using the gift-giving process as a starting point. We conducted empathic interviews about the last time our partner gave a gift, and through those interviews we strove to understand their perspective: what motivates that person, inspires him or her, drives him or her and/or frustrates him or her.

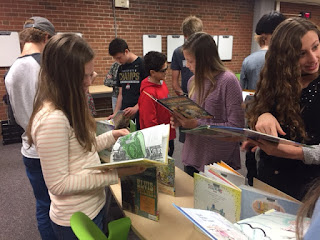

After listening and learning, we narrowed down and defined what we heard, identified what needed to be addressed, and embarked on a boundless ideation process, where we came up with as many ideas as possible to help our partner improve his or her future gift-giving experience. Ideas in hand, we consulted our partner for feedback, learned which ideas resonated and what we needed to improve, merge or eliminate. Then, we pursued a rapid prototype construction of the most promising idea and handed it over to our partner so he or she--and eventually the entire room--could see the physical manifestation of our concept.

|

| Beginning the ideation process |

|

| Constructing a prototype |

|

| Putting all of our prototypes in the center of a circle |

As we reflected on the process, people shared differing reactions. Some found the entire experience liberating because the partner check-ins made it feel more collaborative. In other words, they felt their imperfect design belonged to more than just them. Others felt okay with the messiness because everyone else was in the same boat. And still others struggled with offering up a product before it was perfected.

As we discussed our experiences, Paccione made a case for why it's okay to have imperfect ideas when you're prototyping, because failing early allows you to learn and adapt before you invest a lot of time and emotional energy on something that isn't going to work. Then he went on to share examples of how rapid prototyping has helped Apple and other technology companies in the real world.

Primed and ready for something substantial, he told us it was time to take the process we had just experienced and apply it to our lives. Hoping to task us with something that resonated deeply with students and staff, he called up one of the teachers and asked her to identify what she most wished for in a school. Then he brought up a student.

The two spoke eloquently and passionately and the overlap was unmistakeable.

|

| The Teacher's Wish List is on the Left; The Student's Wish List is on the Right |

From here, we identified a list of How Might We questions to address those concepts, and during lunch, Paccione asked us to put a post-it note on the HMW question we felt most passionate about.

|

| "HMW Bring joy back to the classroom?" is on the left; "HMW break the status quo without causing an uproar?" is on the right. |

Two questions stood out from the rest, and we decided to combine them: How might we break the status quo to bring joy back to the classroom? With our mission on the table, students and teachers came alive. We conducted empathic interviews of one another, learning how much we had in common in our wishes and dreams, how much we both felt the pressure, the dullness, the desire to do bigger things, to spark curiosity and passion, to learn rather than test.

During one of our breaks, a student told me, "It feels so good to know teachers get it, that they understand, that they care about the same things we do, and it would be so awesome if we could really make a change."

Another student told me she wanted time to learn, to think, to explore, but she is so overloaded with what she has to do, she doesn't have time to learn what she wants to.

On one of the post-it-notes a student said we needed to "grade over time not in time," and countless others wrote about how much they yearned for the opportunity to get to know their peers and teachers as human beings, but because we have so many standards to cover, they constantly hear, "you need to know this for the A.P. test."

The entire room itched with the desire to harness what is already human nature: to question, to learn, to understand, to play and to explore. And over and over again, they dreamed of creating a learning space where all of us--teachers and students--come wildly alive.

A place where we all want to wake up and go.

Unfortunately, the bus arrived at 2pm to take this group of brave, insightful and passionate teenagers back to the high school, but the conversations have been preserved on paper and in images, and the spark has been ignited. We are just starting this process, but the potential is limitless and I am so excited to be part of this journey.